Attacco a un ripetitore

Sono già diverse settimane che all’insieme della popolazione viene imposto lo stato d’eccezione, sotto forma di confinamento sanitario, con la sua dose di divieti inediti, d’ipocrisia quotidiana e di promesse di salvezza.

Io non volevo morire di paura e di noia, attaccato a una flebo davanti a Netflix. Nel mese appena passato, la rabbia e la costernazione di vivere in diretta un cattivo romanzo di fantascienza sono diventate per me più che un veleno: un antidoto. Ho quindi deciso di attaccare.

Estendendo le frontiere dell’illegalità, imponendosi ovunque nelle strade, sbirri e cittadini vigilanti hanno trasformato il territorio in uno spazio nel quale abbiamo dovuto riapprendere a spostarci e a trovare il sentiero verso altri/e complici.

Dato che le croci in cima alle montagne sono state rimpiazzate dai piloni della rete GSM e della 5G, questo dice qualcosa della forma che prendono attualmente il potere e le nostre credenze di salvezza.

Era quindi l’ora di riaccendere i fuochi sulle colline, per diffondere dei messaggi più essenziali e diretti, a quelli/e che vorranno ascoltari, l’ora di bruciare queste croci fatte di nodi di fibra ottica e di reti elettriche.

Sono solo/a, da qualche parte sopra la valle dell’Ouvèze, fra Le Pouzin e Privas, domenica 3 maggio [2020], verso le 2.00 del mattino. Nelle ultime ore è piovuto molto e le ultime nuvolette di nebbia che si evapora dal suolo si alzano davanti all’alone di una mezzaluna. La notte è dolce e talmente calma.

In questi ultimi anni sembrava crescere, nei discorsi, l’impressione che lo Stato lasciasse progressivamente il posto a forme di gouvernance più liberali ed economiche, che ad un potere verticale si sostituissero già delle forme più diffuse, invisibili.

Ma lo Stato non è sparito. E’ al centro della realtà, in guerre lontane contro il terrorismo, in Mali, nella promozione di una quotidianità connessa, nella repressione generalizzata dei movimenti sociali, nella produzione di condizioni di vita sempre più normative e tecnologizzate.

All’aurora della nuova primavera, viene dichiarata di nuovo la guerra, come ultima ragione di unione, come causa comune, come dovere di fedeltà. In nome della salute e della sicurezza di tutti e tutte, eravamo destinati/e ad essere riuniti/e, contati/e, suddivisi/e, ordinati/e, assegnati/e, sorvegliati/e e studiati/e.

Chiunque deroghi alla regola imposta da ministri, esperti in salute di ogni tipo, dai prefetti e dalla loro polizia, sarà trattato da irresponsabile che minaccia la salute dei più deboli.

Non è cosa nuova che, in nome delle persone giudicate e classificate come «fragili», il potere si ritagli il suo ruolo migliore. Il potere è ambidestro. Tende la mano che protegge, quella che salva e coccola. Allo stesso tempo, colpisce e mutila. Sentiremo presto dire che ci sono delle tecniche di gestione statale della crisi migliori di altre. Si compara quello che succede a latitudini diverse. Si incriminano i poteri più totalitari, come in Cina e in Brasile. Ci si felicita del fatto che in Portogallo le istituzioni davano dei documenti a tutti i richiedenti asilo. Quasi quasi, non ci si sente poi così male, qui da noi.

Avanzo calmo/a nella penombra, qualche litro di combustibile nello zaino, una tronchese pesantemente posizionata contro la mia colonna vertebrale. Sono come assente a me stesso/a, assorto/a nel silenzio e nei mormorii notturni, preso/a dall’accuratezza dell’attività, poso i miei passi senza lasciare tracce. La cima è tranquilla. Una brezza leggera spazza la cresta, da dove vedo, ovunque in basso, il lampeggiare delle diverse installazioni elettriche della zona, campi di pale eoliche, ripetitori telefonici e pianure industriali.

Mi apro un cammino nella griglia, spaccando una catena che blocca la porta del recinto principale e della più grande delle due antenne. Preparo il materiale e faccio attenzione a rimanere al sicuro da sguardi indiscreti, sotto il passamontagna.

Avanzando, continuo a pensare: come in ogni «crisi», che sia prodotta dal nulla dal potere oppure subita e gestita come gli riesce meglio, la situazione crea un contesto inedito, un supporto per la costruzione degli anelli mancanti nel meccanismo del progresso. Centinaia di scienziati, di medici e di ingegneri-biologi sono venuti a proporci, per il nostro bene, delle ricette di balsami miracolosi, da ciarlatani del ventunesimo secolo. Molto più che venderci una qualunque medicina, ci vendevano delle ragioni per continuare ad avanzare, delle maniere di vivere. Nella sua risposta all’ira degli dei, la scienza si è offerta piena di promesse, apportando soluzioni innovative alle problematiche prodotte dal progresso.

Il dispotivo sanitario opera anche una selezione fra maniere di morire che sono accettabili oppure no. I rischi nucleari e industriali, organizzati e costitutivi dell’attività umana, contrariamente alla maggior parte dei rischi biologici, producono morte e sofferenza ogni anno, verosimilmente in quantità davvero importante. Dov’è lo Stato benevolo e protettore, quando si tratta di proteggere i suoi cittadini dai tecnocrati del nucleare?

Di fronte a discorsi che possono parere vani o a volte mancare, le mie mani guantate fanno scivolare dei pacchetti di diavolina industriale sotto liane di cavi.

Vi verso anche del gel accendifuoco e mi volto verso l’uscita del recinto, per avvicinrmi alla seconda antenna. Un mini-escavatore, fermo per la notte, è naufragato al bordo del sito. Mi spiace non poterlo prendere di mira e mancare di materiale. Piazzo di nuovo dei dispositivi incendiari sui cavi più fragili e ritorno alla prima antenna.

Una volta sul posto, inzuppo bene il tutto con della benzina ed accendo, da una parte e dall’altra della struttura, due fuochi che la brezza gonfia progressivamente.

Scendo alla seconda antenna ed opero nello stesso modo.

Mi allontano dal sito e sparisco nella notte.

La salute e la sicurezza sono diventate poco a poco i valori supremi che giustificano, da loro sole, gli sforzi e gli errori più assurdi.

Il virus e la lotta contro la sua propagazione, per il fatto che esso incarna la morte che plana e che colpisce a caso, imprevisibile ed improvvisa, è diventato lo spettro da cacciare senza tregua, aumentando di continuo i limiti dei luoghi che siamo pronti ad evitare per non morire.

Quello che è stato interiorizzato, come esperienza collettiva, e forse in maniera definitiva, sono il gusto e la necessità del sacrificio. D’ora in poi, ci chiederanno in continuazione di svendere i brandelli rimasti delle nostre vite, per non perderle.

A posteriori, non so se questo attacco ha causato dei danni importanti. Magari solo qualche cavo sezionato. Quello che conta, per me, è il fatto di essere riuscito/a ad agire, anche da solo/a, di essere riuscito/a, in questa notte strappata all’assurdo, a superare i miei dubbi e le mie angosce ed aver colpito quello che sembra essere, oggi, un nodo esenziale della società attuale: la rete di telefonia mobile e l’insieme del mondo connesso che essa permette.

Contro la società del controllo e la dittatura sanitaria.

Ho un pensiero di rabbia verso i tablet e i robot di assistenza medicale che è ormai di moda distribuire in gran numero nei mortori per persone anziane. Che le ultime persone che hanno attraversato questo secolo senza tecnologia muoiano circondate da robots e da applicazioni di ogni tipo, mi dà voglia di vomitare. Le linee di satelliti, spediti in orbita a migliaia di esemplari, che sabotano i misteri del cielo notturno, non saranno mai delle promesse di pace.

Un pensiero per le porte che restano volontariamente aperte, in questo perdiodo difficile, per quelle e quelli che cercano, costi quel che costi, di non sacrificare le loro vite davanti alla paura. Ai colpi resi e ai colpi di mano. Ai brutti colpi ed ai colpi andati storti. A quelli/e che ci provano. A quelli/e che magari non attaccano, ma che aiutano a continuare e che infrangono le ovvietà.

E allora: smettere di vivere? Piuttosto morire!

[Rivendicazione in francese pubblicata in attaque.noblogs.org].

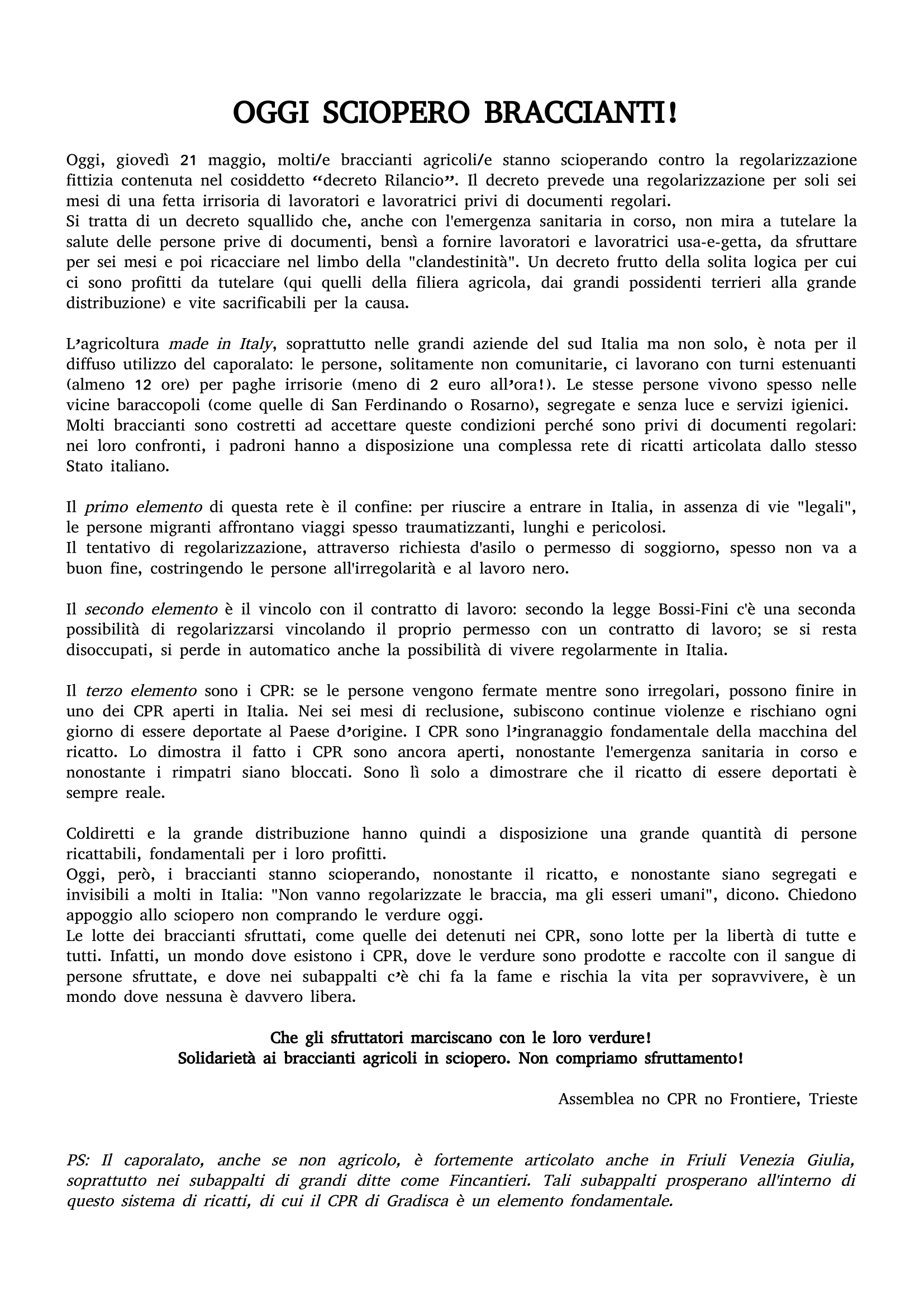

Oggi, giovedì 21 maggio, molti/e braccianti agricoli/e stanno scioperando contro la regolarizzazione fittizia contenuta nel cosiddetto “decreto Rilancio”. Il decreto prevede una regolarizzazione per soli sei mesi di una fetta irrisoria di lavoratori e lavoratrici privi di documenti regolari.

Oggi, giovedì 21 maggio, molti/e braccianti agricoli/e stanno scioperando contro la regolarizzazione fittizia contenuta nel cosiddetto “decreto Rilancio”. Il decreto prevede una regolarizzazione per soli sei mesi di una fetta irrisoria di lavoratori e lavoratrici privi di documenti regolari.